One of the best scenes in Queen & Slim takes place in a bar in Georgia. Queen (Jodie Turner-Smith) and Slim (Daniel Kaluuya) are a young couple on the run, having killed a policeman in self-defence. This bar offers them some respite, allowing them to drink, dance and momentarily forget their perilous situation, and it is entirely populated and owned by black people. “Don’t worry,” the proprietor tells Slim, handing him drinks on the house. “You’re safe here.”

Read the rest of my Sight & Sound review here

Phil on Film Index

▼

Thursday, January 30, 2020

Friday, January 17, 2020

Robert Pattinson on The Lighthouse

In the same year that the Twilight saga ended, Robert Pattinson starred in David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis (2012), and it felt like a statement of intent from a young actor determined to take control of his career. Pattinson is a risk-taker who is drawn to directors with unique visions and roles that push him to extremes, and The Lighthouse is the latest chapter in an increasingly impressive body of work.

Read my Sight & Sound interview with Robert Pattinson here

Read my Sight & Sound interview with Robert Pattinson here

Wednesday, January 08, 2020

1917

The last time Sam Mendes went to war it was with Jarhead (2005), an adaptation of Anthony Swofford’s Gulf War memoir, and it was a film defined by stasis, with its battle-ready marines sinking into frustration, boredom and delirium as they waited for their promised conflict to materialise. A similar approach might have been appropriate for a film about the Great War – a war of attrition in which men spent months inching through trenches and tunnels – but instead 1917 is a work of propulsive forward motion and non-stop action.

Over the course of 24 hours, Lance Corporal Schofield (George MacKay) must escape from a collapsing trench, avoid being hit by a crashing plane, take out an unseen sniper, kill a man with his bare hands, jump into a ferocious river (which takes him over a waterfall, naturally) and race across the frontlines as shells explode around him. It’s World War I: The Ride. When giving Schofield his orders, General Erinmore (Colin Firth) quotes Rudyard Kipling – “Down to Gehenna or up to the Throne, He travels the fastest who travels alone” – and the haste with which Schofield sprints through much of the film suggests he might be on to something.

Read the rest of my review on the Sight & Sound website

Over the course of 24 hours, Lance Corporal Schofield (George MacKay) must escape from a collapsing trench, avoid being hit by a crashing plane, take out an unseen sniper, kill a man with his bare hands, jump into a ferocious river (which takes him over a waterfall, naturally) and race across the frontlines as shells explode around him. It’s World War I: The Ride. When giving Schofield his orders, General Erinmore (Colin Firth) quotes Rudyard Kipling – “Down to Gehenna or up to the Throne, He travels the fastest who travels alone” – and the haste with which Schofield sprints through much of the film suggests he might be on to something.

Read the rest of my review on the Sight & Sound website

Tuesday, January 07, 2020

Amanda

These emotional states are allowed to unfold organically in Amanda – nothing feels forced, even if the incident that ruptures their lives is such a spectacular and catastrophic one. Amanda's mother Sandrine (Ophélia Kolb) is one of the many victims of a terrorist shooting in a Paris park, and David likely would have suffered the same fate if a delayed train hadn't meant he was cycling towards the carnage as the perpetrators were speeding away in the opposite direction. The act itself happens off screen, we only stumble upon the shocking aftermath as David does, and an eerie stillness descends on this portion of the film, which is at odds with the vibrancy Hers had established in the earlier scenes, aided by the warmth and richness of Sébastien Buchmann's 16mm cinematography.

Of course, having Sandrine suffer a sudden untimely death by any means could have produced a similar effect, but the use of a terrorist attack allows Hers to draw a wider portrait of a community in mourning, showing both its vulnerability and resilience. We meet other survivors who are coping with their injuries in different ways. The once-confident Léna (Stacy Martin) becomes tentative and nervous, withdraw from the romantic relationship she had begun with David and deciding that she needs to leave the capital to recuperate in the countryside with her mother, while David's friend Axel (Jonathan Cohen) admits that his injury has briefly bolstered a marriage that had been on the rocks. Hers doesn't attempt to dig into the wider political context of terrorism aside from a brief glimpse of a Muslim woman being berated in the street, which leads Amanda to ask David questions about their faith – one of the film's few awkward steps – but he does create a real sense of lives being lived beyond the frame.

Expertly edited by Marion Monnier, Amanda proceeds at a gentle, fluid pace and Hers maintains a measured tone throughout, keeping emotional outbursts or dramatic developments to a minimum but capturing moments that feel extraordinarily specific and authentic. Hers and his actors frequently display fine judgement and sensitivity as they explore this emotionally complex territory. Lacoste makes subtle adjustments to portray his character's developing maturity and stability, while Kolb creates a vivid enough impression in the film's opening half-hour to ensure her absence is felt thereafter. But it's the title character, played by Isaure Multrier, who emerges as the heart of the film. Multrier appears on screen as an unaffected, ordinary child, and all of her reactions feel completely real. In the deeply moving final scene she recalls something her mother said right at the start of the movie, something David can't understand, again suggesting the inner life and private sense of mourning that makes these characters feel so fully realised. My heart broke for her, but Hers leaves his audience in the same delicate place that he leaves his characters – heartbroken, but hopeful.

Monday, January 06, 2020

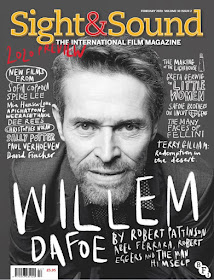

Sight & Sound - February 2020

I've got a couple of articles that I loved writing in the latest issue of Sight & Sound. During last year's London Film Festival, I had the opportunity to meet the great Willem Dafoe to discuss his new film The Lighthouse and to look back at one of the most adventurous careers in the business. Aside from his latest film, our conversation touched on his pursuit of fresh challenges, his relationship with Abel Ferrara, his thoughts on distribution and television and more, and he was such an engaging and thoughtful interviewee. I also really enjoyed interviewing The Lighthouse director Robert Eggers and Dafoe's co-star Robert Pattinson for this feature.

Elsewhere, you can read my report from the set of Terry Gilliam's The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. I spent a memorable day in Portugal watching Gilliam shoot his long-awaited film back in 2017, and now it's finally reaching UK cinemas I'm delighted to be able to share my experience. If you'd like to read an interview with Terry Gilliam that doesn't solely consist of him ranting incoherently about political correctness, then this is the article for you!

I also reviewed a couple of new releases: 1917 and Queen & Slim. You can read all of this in the February issue of Sight & Sound, which is on sale now.

Elsewhere, you can read my report from the set of Terry Gilliam's The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. I spent a memorable day in Portugal watching Gilliam shoot his long-awaited film back in 2017, and now it's finally reaching UK cinemas I'm delighted to be able to share my experience. If you'd like to read an interview with Terry Gilliam that doesn't solely consist of him ranting incoherently about political correctness, then this is the article for you!

I also reviewed a couple of new releases: 1917 and Queen & Slim. You can read all of this in the February issue of Sight & Sound, which is on sale now.