New Films Seen This Week

Assassin's Creed (Justin Kurzel)

The films of Justin Kurzel have been relentlessly dour thus far, which is perhaps unsurprising given his choice of subject matter. Snowtown and Macbeth were both brutal tales full of violence, but Assassin's Creed is an action-packed, time-travelling video game adaptation! Shouldn't it be a little bit fun? Sadly, 'fun' doesn't appear to be in Kurzel's repertoire. In Assassin's Creed, a number of fine actors spend an awful lot of time standing around, peering impassively through windows and flatly delivering expositional dialogue. They all seem to be waiting for something to happen, and when it does it's not really worth waiting for. When Cal (Michael Fassbender) is transported back to 1492 and into the body of his ancestor, a shadowy assassin determined to stop the Knights Templar from finding the Apple of Eden, the film collapses into a series of CGI-enhanced fight and chase sequences – sometimes taking on the structure and style of a video game – that have been edited into complete incoherence. None of this overblown nonsense seems to sit well with Kurzel, and even the director's keen eye has deserted him here: the 15th century scenes are all cast in dull browns and yellows and shrouded in smoke, while the modern-day section of the film is set in a steely grey/blue generic scientific facility. There is some talk in Assassin's Creed of free will versus our willingness to give up our freedoms for our security, but it's hard to know what Kurzel, the three screenwriters, and the powers that be at Fox are trying to say or do here; the film is so stylistically confused and so bogged down with the dreary machinations of its own confounding plot. Perhaps Fox once had thoughts of starting a blockbuster franchise with this film – the ending certainly implies further adventures are forthcoming – but their decision to dump it in January feels like more of a mercy killing.

A Monster Calls (J. A. Bayona)

If the numbers available on the internet are to be believed, A Monster Calls cost roughly a third of Assassin's Creed, and yet the visuals are more impressive and imaginative than anything Kurzel's film can muster. The Monster at the centre of the film is a huge and strikingly rendered creature that emerges from an ancient yew tree outside the house of Conor O'Malley (Lewis MacDougall), and when he tells Conor his fantastical tales they are brought to life on the screen through watercolour-style images that reflect the artistic bent shared by Conor and his dying mother (Felicity Jones). It's easy to admire the sense of ambition behind J. A. Bayona's adaptation of the novel by Patrick Ness, as it attempts to tell a story about the importance of facing up to grief that can appeal to a younger audience; in fact, there's plenty to admire about A Monster Calls – the filmmaking and the performances are solid throughout – but the film never really comes together at all. While he has been wonderfully animated, and is voiced with suitable gravitas by Liam Neeson, the Monster proves to be a bit of a one-note mentor, and his parables repetitively hammer home the same ideas, until it comes as something of a relief when the third story is oddly curtailed. The fantasy and reality elements of the movie fail to mesh in any interesting way and they feel like two disparate movies awkwardly stuck together. The film is on slightly firmer ground in the real world, but the characters have no sense of inner life and no dimensions beyond what we are initially presented with; only Sigourney Weaver – introduced as an uptight harridan, just so she can soften – gives her character any kind of emotional shading. A Monster Calls feels fatally torn between bombast and emotion, delivering spectacular set-pieces but failing to give the characters the depth required to make their wrenching situations hit home. It builds to a noisy climax that seems determined to extract tears from the audience by sheer force, and it's hard to avoid getting caught up in the spectacle, but instead of feeling moved by Conor's story I just felt bludgeoned and frustrated by a showy, empty spectacle.

Rep Cinema Discovery of the Week

Jailhouse Rock (Richard Thorpe, 1957) Prince Charles Cinema, 35mm

There's not much to beat black-and-white CinemaScope on a nice 35mm print. What surprised me about this simplistic but enjoyable star vehicle is how unlikable Elvis is for most of the film’s running time. He kills a guy (albeit accidentally, and in defence of a woman) in the film’s opening moments, he is sent to jail where he becomes a star through a nationally televised talent show (?), and then he is freed to begin his singing career, where he arrogantly discards anyone who helped him along the way. “How dare you think such cheap tactics would work with me!” Peggy (Judy Tyler), his promoter and partner, complains after he has roughly kissed her. “That ain't tactics, honey. It's just the beast in me,” he replies. He’s surly and inconsiderate to everyone he meets, and the comic highlight of the movie comes when he causes a ruckus at a dinner party after the posh guests ask him for his opinion on Jazz (“Lady, I don't know what the hell you're talking about!”). A punch in the throat eventually straightens this young buck out right at the end of the movie. In his third feature, Presley is actually pretty good in the lead role. His undeniable star quality carries the movie and everyone else involved the picture is conscious of the fact that they are simply there to support him. MGM workhorse director Richard Thorpe doesn’t do anything imaginative with the CinemaScope frame, he simply keeps things chugging along from one scene to the next, and the only person who threatens to steal the young king’s limelight is the charming Tyler, with whom he shares a sparky chemistry. Tragically, what looked set to be a breakthrough role for the young actress proved to be her swansong, as she and her husband were killed in a car crash before the film opened. “Nothing has hurt me as bad in my life,” Elvis later said. “All of us boys really loved that girl… I don’t believe I can stand to see that movie we made together now, just don’t believe I can.”

Rep Cinema Rediscovery of the Week

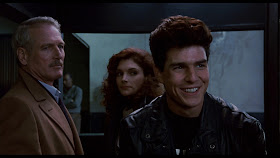

The Color of Money (Martin Scorsese, 1986) BFI Southbank, 35mm

The Color of Money might not be peak Scorsese, but it’s certainly undervalued Scorsese. A studio gig that the director took in the mid-80s as he tried to get The Last Temptation of Christ off the ground, the film feels more inconsequential than most of his pictures but it also feels loose and liberated. It’s a fun movie, and part of the fun is in watching two very different movie stars at the opposite ends of their career playing off each other. Reprising the ‘Fast’ Eddie Felson character 25 years after The Hustler, Paul Newman has a weary, seen-it-all quality here, but a chance encounter with Tom Cruise’s sensationally talented Vince gets his juices flowing again. Cruise is all cocky swagger, but there’s also a naïve, petulant quality that comes through in his performance, particularly when Eddie toys with his emotions over his relationship with the savvier Carmen (an excellent Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio). Vince knows how to play pool, but Eddie knows the secret is to play people, and the film is very absorbing when it focuses on these three complex, vividly realised characters and the fascinating dynamic between them (Helen Shaver, as Eddie’s on-off girlfriend, never quite comes to life). The pool sequences are exhilarating, with Michael Ballhaus’s camera roving around the players and Thelma Schoonmaker cutting shots together into a blizzard of clicking balls. The Color of Money runs a little too long but it’s a great piece of entertainment; slick, smart and superbly made. In an age when unnecessary sequels resurrecting decades-old characters are de rigueur, we can only dream of them being made with such artistry, being aimed at adults, or being built around a movie star who can command the screen as effortlessly as Newman does here.