A packed schedule has taken its toll on my LFF updates, with my own habitual procrastination hardly helping matters either. This is the penultimate roundup, and I'll be writing full reviews for the most notable films in the festival – including A Serious Man, About Elly, The Disappearance of Alice Creed and Mother – closer to the films' respective release dates. For now, here's my two cents on everything else.

The Last Days of Emma Blank (De laatste dagen van Emma Blank)

The Last Days of Emma Blank (De laatste dagen van Emma Blank)

Emma Blank is dying, but if she's going to die, she's going to do it her way. In a manor house somewhere in the Dutch countryside, this steely matriarch (played by Marlies Heuer) has persuaded her entire family to wait on her hand and foot until she passes, literally behaving like slaves and putting up with every one of Emma's demands no matter how absurd. She has even persuaded one poor sap to behave like the family dog. It quickly emerges that the reason they are putting up with such behaviour is, of course, money, with Emma ready to leave a large amount behind her when she finally shuffles off to the other side. There is plenty of deadpan, surreal humour to be derived from this setup, and some interesting tensions between the various characters, but Alex van Warmerdam doesn't seem entirely sure of where he's taking his story, and the film's joke wears thin after a while. The performances are strong, with Eva van de Wijdeven making a particular impression as Emma's rebellious daughter, while the director himself makes an amusing cameo as Theo, the family dog.

Shirley Adams

Shirley Adams

Reminiscent of the Dardenne brothers, this South African drama utilises a handheld style, with the camera permanently perched behind the shoulder of the titular character. Played by Denise Newman, Shirley is a single mother of a teenage boy who was left paralysed from the neck down after a shooting incident. Writer/director Mark Hermanus convincingly captures the difficulties of this relationship, with Keenan Arrison impressively portraying the frustrated, embarrassed Donovan, cringing as his mother washes and dressing him. We watch as Shirley struggles to get by alone, her pride preventing her from asking for help, and she even resorts to shoplifting at one desperate point, before finally relenting and allowing care worker Tamsin (Emily Child) to enter their home and assist with Donovan's recuperation. Hermanus' direction is intimate and unflashy, although his habit of peeking around corners and doorframes feels like something of an affectation. There's nothing remotely affected about Newman's central performance, though, whose face alone reveals so much about the hardship her character has endured.

The French Kissers (Les beaux gosses)

The French Kissers (Les beaux gosses)

Imagine a French version of American Pie – a Tarte Français, perhaps – and you'll have an idea of the tone the makers of The French Kissers are going for. The central characters are two pimply, sullen teenagers desperate to get laid, but it's hard to support them in their quest as Hervé (Vincent Lacoste) and Camel (Anthony Sonigo) are two of the most charmless yokes imaginable. Various scenes of embarrassment and humiliation ensue, as the two teens are constantly thwarted in their romantic endeavours, but very little of it is actually funny. The best performance in the film comes from Noémie Lvovsky as Hervé's interfering mother, who shares a lively, almost incestuous relationship with her son, but the rest of the film is flat and unimaginative, and the storytelling is slapdash. I was briefly cheered by the appearance of Irène Jacob – beautiful as ever – as the mother of Hervé's on-off girlfriend, but alas, it's nothing more than a cameo.

Plan B

Plan B

I don't make a habit of walking out of films, but I was struggling to care about Plan B pretty much from the start, and after an hour I decided to quit while I was behind. The setup is contrived and a little silly – jilted Bruno (Manuel Vilna) plans to end his ex-girlfriend's new relationship by seducing her new man Pablo (Lucas Ferraro) – but there's surely potential within it for a decent farce. Exploiting that potential would have required a great deal more wit, timing and daring than writer/director Marco Berger seems capable of producing, though. The purpose of Bruno's plot is poorly developed (Laura is still sleeping with him behind Pablo's back anyway, which seems to lower the stakes somewhat) and there isn't enough chemistry between the two male leads to make their awkward scenes together work. Apart from all of that, the film is crippled by Berger's astonishingly sluggish pacing, and by the time Pablo had discovered the true nature of his new friend's intentions, I decided that waiting to see how the next 45 minutes would pan out would not be a productive use of my time when I had so much else to do.

Karaoke

Karaoke

Following that little lapse, let's move on to the only film I fell asleep during in this year's programme. Karaoke begins in a rather bewildering fashion, and while things may have been clarified shortly afterwards, I'm afraid I'm not a reliable enough witness to confirm that. Here's what I managed to get before the weight of my eyelids defeated me: a mother and son are working in a karaoke bar, he has a sideline filming the karaoke music videos, and he likes to take long walks through the woods. And I mean long walks. In the end, I think my hectic schedule got the better of me, and I dozed peacefully for most of Chris Chong Chan Fui's film. I was particularly disappointed to miss so much of Karaoke because it's the first Malaysian film I've ever seen – or half-seen, as it turned out.

J'Accuse (1919)

J'Accuse (1919)

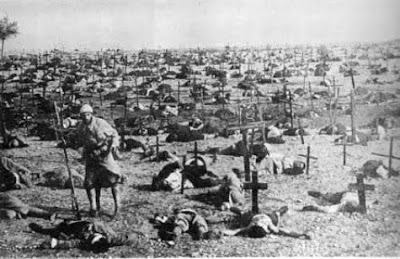

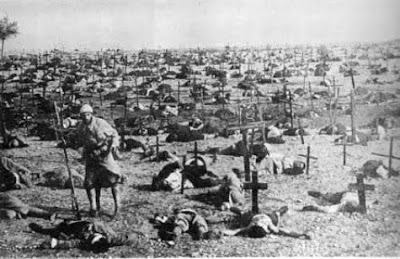

While the London Film Festival's main focus is on new films from all corners of the globe, one of its most fascinating strands every year is the archive section, in which old films are screened in newly restored prints. I've got three in my schedule this year, two of which are detailed in this roundup, with John M. Stahl's Leave Her to Heaven to come later in the week. On Saturday, I finally saw a film I had been aching to see for years, Abel Gance's 1919 film J'Accuse. Shot in the final year of the first world war, the film's authenticity is unmistakable, with Gance filming on the battlefields of Europe and using real soldiers as extras (80% of these men were dead within days). These scenes provide the backdrop to a romantic melodrama featuring the brutish François (Séverin-Mars) and the poet Jean Diaz (Romuald Joubé), who is in love with François' wife Edith (Maryse Dauvray). The plot is simplistic but the greatness of J'Accuse exists in Gance's stunning orchestration of the action. His direction is ambitious and visually striking; from the opening shot of hundreds of soldiers sitting down to spell out the title, to the recurring motif of skeletons dancing across the screen, and the disturbing sequence in which Edith is raped by German troops, whose elongated shadows loom over her. As brilliant as his filmmaking is throughout, nothing could have prepared me for the stunning climax, where the corpses of the dead rise from their graves to see if the people they have fought for have lived up to their sacrifice. A magnificent film, which has only further whetted my appetite to finally see Gance's epic Napoléon on the big screen. I must finally mention the contribution of Stephen Horne, who performed brilliantly on the piano and flute throughout, his music merging seamlessly with the onscreen action.

Underground (1928)

Underground (1928)

This year the London Film Festival is holding an archive gala screening for the first time, and the rarely seen Underground was a perfect choice for the slot, with the focus of the festival shifting to the Queen Elizabeth Hall for one night only. A collection of introductory clips detailed the work required to repair and restore the four heavily damaged source prints that have gone into this pristine new version – and pristine is the word, it looks thoroughly amazing. Underground was Anthony Asquith's first sole effort as a director, made when he was just 26 years old, and he directs with the same flair and invention that Orson Welles would later do at the same age. The film is set mostly on the London Underground, with Asquith portraying it as a medium through which travellers of all types and classes rub shoulders on the daily commute. The plot itself is simplistic but compelling. Tube porter Bill (Brian Aherne) and power station worker Bert (Cyril McLaglen) fall for Nell (Elissa Landi) on the same day, and when she makes her choice, the jilted Bert persuades unstable seamstress Kate (Norah Baring) to help him discredit Bill and end the relationship. The film is stylishly and energetically directed by Asquith, displaying the legacy of his European influence through his imaginative camerawork, sharp editing and deeply impressive lighting techniques. Certain set-pieces stand out; notably the pub brawl scene – featuring some brilliant work from the extras – and a tense climactic chase sequence. The whole night was one of my most memorable LFF experiences, with Neil Brand and his Prima Vista Social Club band performing Brand's new score to accompany the screening, and contributing to the electric atmosphere inside the auditorium. I ended the evening by getting an invite to my first (and only) LFF party this year, where I spent some time chatting to both Brand and the great Terence Davies.

Surprise Film

Surprise Film

Here's the story. The 2009 LFF Surprise Film was due to screen on Sunday night, and I had a ticket, but I decided to offer it to a friend who really wanted to go because I was also due to attend another surprise screening on Monday, which had been arranged exclusively for BFI members. When I heard that Sunday night's film turned out to be Capitalism: A Love Story, I felt I'd dodged a bullet, but when I got to the NFT the following night, rumours had already begun circulating that it would turn out to be exactly the same film. Sandra Hebron pretty much confirmed this in her introduction, calling it "The surprise film that might not be much of a surprise," and when the movie began, a number of people got up and left, having sat through the picture already one night previously. It certainly seemed like a short-sighted move on the part of the organisers – didn't they imagine some people would like get tickets for both screenings? Mind you, the remarkable demand for tickets on both nights has further bolstered my belief that a film festival consisting entirely of surprise films would be a massive hit; people can't seem to resist the lure of uncertainty.

As for the movie – well, it's Michael Moore, what else do you need to know? His take on capitalism bears all of the worst excesses of the director's previous works. The tone alternates between sarcasm and faux-naïveté, the links between Moore's arguments are clumsy, there's an overreliance on comically voiced stock footage, and there's even the shameless milking of a child's tears to ram his point home. Moore spends much of the film's second half standing outside a building holding a bullhorn, before being turned away by security guards, and if he had simply cut those pointless scenes, this overlong film might have been more bearable. The director never builds a coherent argument out of the scraps of evidence he has come armed with, and his message is woefully inconsistent (he damns the government for fear-mongering, before lining up a bunch of Catholic priests to tell us capitalism is a sin), but ultimately Capitalism just feels a little dated. Although a couple of Moore's anecdotal sequences are interesting, there's nothing revelatory about his film, not after a year of news coverage focusing on the financial collapse. I'm just glad I gave away my Sunday night ticket; I'm not sure I could have endured this twice.

Atom Egoyan has made some poor films in his career, but at least they were his poor films, as much a product of the director's own personality and obsessions as his best work was. I never had him down as a hack-for-hire, but with Chloe we find the director wasting his time on some sub-Joe Eszterhas silliness that can't be glossed up into anything more, no matter how hard Egoyan tries to impose his own artistic sensibility on it. The film is a remake of Anne Fontaine's 2003 drama Nathalie... (one of the worst films I've ever seen), and the saving grace of Chloe is that it is a marked improvement on the original, as meagre an achievement as that may seem. It is also one of Egoyan's most accessible and potentially mainstream-friendly works, but that still doesn't mean it's any good.

The French version of this tale starred Fanny Ardant and Gérard Depardieu as a married couple, with Emmanuelle Béart appearing as the eponymous character, a prostitute hired by Ardant to seduce her husband and to report back – in excruciating detail – if he succumbs to her charms. Erin Cressida Wilson's updated screenplay keeps the bare bones of the tale intact, with Julianne Moore and Liam Neeson taking on the spousal duties. Moore's Catherine is an unhappy and frustrated gynaecologist, who can't connect with her moody teenage son and who fears her husband may be straying now the spark has gone out of their marriage. David is a charismatic university professor who is adored by his students, and a few scraps of evidence suggest to Catherine that he is having an affair with one of them, which is when she does what any wronged wife would do...she hires a hooker. A hooker who, it turns out, is far more interested in Catherine than her husband.

Chloe feels like a warmed-over plot from an early 90's erotic thriller, which Egoyan tries to elevate with his typically elegant direction, but the performances are the only aspect of the film he really gets right. Julianne Moore gives her finest display for years as the brittle Catherine, once again showing that few actresses can play a character who is barely holding it all together better than she can. Neeson is fine in a role that doesn't give him a great deal to do, but Amanda Seyfried, as Chloe, is slightly more problematic. She's perfectly OK in the film earliest scenes, when she plays the role as something of an enigmatic blank; after all, this is one of the character's traits, being a blank canvas that men can project their own fantasies onto. But when she is required to turn Chloe into something more than that – i.e. when the film lurches into Fatal Attraction territory – she falls short of what's required.

And so does Egoyan. For about an hour, Chloe is watchable enough, if entirely generic and rife with clichés, but in its final half-hour, we see just how ill-suited the director is to material of this nature. While this story does allow him to explore some of his favourite themes – voyeurism, sexual obsession, trust – his clinical seriousness makes this essentially trashy material seem even more absurd, and the whole film feels oddly uneven in tone. But it's that climax which really throws the whole off the rails, with Egoyan being unable or unwilling to give the ending the kind of pulpy energy it requires, and the Hand That Rocks the Cradle-style dénouement is laughable as a result. Perhaps you could make a case for Chloe's themes and subject matter being a good fit for this auteur's body of work, but whatever it was that Egoyan will claim attracted him to this material, it ends up looking like botched, impersonal hackwork, which is depressing when it has been made by a man who is anything but.

What a difference an exclamation point makes. If you saw a film entitled The Informant, you might expect a serious and dramatic undercover thriller, but in calling his film The Informant!, Steven Soderbergh has prepared us for an altogether goofier take on the material. The irreverent tone is established right away, with the credits and captions appearing in a large, cartoony font, and the score by Marvin Hamlisch is a jaunty, retro affair that initially seems at odds with the material. These seem like typically playful stylistic choices on Soderbergh's behalf, but we quickly come to realise that they suit the story perfectly; the bizarre twists and turns that occur in the tale of Mark Whitacre are simply too weird to be played straight.

Whitacre (played by a chunky Matt Damon) was a top executive at ADM in the early 1990's, who informed the FBI of a price-fixing scandal in the corn industry. You may well wonder why on earth a senior figure at a major company, earning over $350,000 a year, would help bring down his own firm, and a couple of agents at the Bureau did have the same thought. Agent Brian Shepherd (Scott Bakula), however, was convinced by Whitacre's homeliness, and his professed desire to take down the culture of corruption surrounding him, and he coordinated a sting operation in which Whitacre recorded key ADM figures plotting with other companies to raise the price of lysine. The evidence was gold, but this is where the story starts to get weird. It turns out Whitacre is not the most reliable of witnesses, and he has been less than forthcoming about his own financial indiscretions. These revelations threaten to scupper the entire investigation, but throughout it all, Whitacre retains the same chirpy, optimistic demeanour.

His personality dictates the tone of The Informant!, which bounds along with infectious enthusiasm, and Soderbergh allows us to view the story from Whitacre's point-of-view, by adding an eccentric, discursive voiceover reflecting the character's thought process. From any simple starting point, Whitacre can ramble off on a tangent; he queries the correct pronunciation of the word Porsche, wondering how polar bears know to cover their nose in the snow ("That seems like an awful lot of thinking for a bear"), or pondering Japanese girls' underwear. It's a treat to see a filmmaker using voiceover in an imaginative and pointed way, rather than simply using it as a lazy form of narration, and this clever aspect of Scott Z. Burns' screenplay establishes Whitacre as the ultimate unreliable narrator right from the start. The other achievement of Burns' script lies in the way it manages to negotiate the murky world of ADM and Whitacre's chicanery, introducing new revelations in every second scene late on, without creating confusion or collapsing under the weight of it all.

Damon has great fun with his character, bringing an innate likeability and endearing optimism to someone who is essentially a crook, but it's hard to really get a fix on his who this person is. This is because Whitacre doesn't seem have much of a character. He's a fantasist who imagines himself as the hero of his own story ("Like in a Crichton novel"), but I'm not sure the film gets at the heart of Mark Whitacre beneath those levels of deceit, even if it's fun to watch Soderbergh and Damon peeling back the layers anyway. The whole film is a bit like that; it's a glib, very amusing entertainment, which the director handles with his customary class and wit, but its shallowness prevents The Informant! from being anything more than an enjoyable diversion.

The first week of the 2009 London Film Festival has thrown up some fascinating features, and I'll be writing full reviews for Balibo, The Road, Enter the Void, Up in the Air and Dogtooth in due course. In the meantime, here are a few other movies I've caught in the past few days.

45365

The title refers to the postal code of Sidney, Ohio, and this is where local filmmakers Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross spent 9 months filming everyday goings-on, which they have skilfully edited into this engaging documentary. The footage has been assembled in an impressionistic manner, offering us brief slices of life before cutting away to another, seemingly unconnected incident. Two narrative strands give the documentary a sense of shape – a judge's re-election campaign, and the fortunes of the high school football team, as they prepare for a big game – but the film is actually at its best when it moves away from those stories into more humdrum territory. An amusing scene involves a group of elderly women in a care home discussing men, while a couple of interesting sequences concern a mother's quarrelsome relationship with her wayward son. The camerawork is effective and occasionally alights on something beautiful, while the editing is slick, with one breathtaking cut standing out towards the end. There's also an infrequent David Lynch-style weirdness to 45365, which enlivens a few of the duller segments, and I just wish we got a peek at the 29-inch woman, whose presence is tantalisingly advertised at the country fair.

Adrift (Choi voi)

As soon as Hai (Duy Khoa Nguyen) falls into a drunken stupor on his wedding night, we instantly suspect his marriage to Duyen (Do Thi Hai Yen) will not be a particularly satisfying one, and so it proves, with the marriage remaining unhappy and unconsummated. When she seeks solace with her friend Cam, Duyen finds herself being pushed into the arms of Cam's former lover Tho (Johnny Tri Nguyen), a serial womaniser, who can give her the sexual gratification that her marriage is failing to provide. Although the male characters in this slow-moving drama don't really develop beyond their initial dimensions, the female figures are richly drawn, and superbly played by the lead actresses. Director Bui Thac Chuyen handles Phan Dang Di's screenplay in a subtle and lyrical fashion, and he manages to make his film erotic without indulging in any explicit sexual acts. The drama could do with a little more juice, but this is still a solid, adult piece of work.

No One Knows About Persian Cats (Kasi az gorbehaye irani khabar nadareh)

No One Knows About Persian Cats (Kasi az gorbehaye irani khabar nadareh)

The current front-runner for my unofficial LFF Best Title award (I also like the Japanese film Ultra-Miracle Love Story, but that loses points for adopting the much blander English name Bare Essence of Life), No One Knows About Persian Cats is a fictional narrative apparently derived from factual incidents. With pop music being banned in Iran, young Iranians who do want to make music have been forced underground and out of the country. Bahman Ghobadi has constructed his film around a group of indie musicians forced to turn to the black market in search of the visas and passports that will allow them to perform in the west. Although the performances from the bootleggers they come into contact with are amusing, the lead characters of Negar and Ashkan are underdeveloped, as is the storyline they are involved in. Occasionally, Ghobadi disrupts the realist aesthetic to portray a band's performance in a music video-style; although I can't say any of these performances were especially memorable.

We Live in Public

We Live in Public

Josh Harris is a fascinating individual, and We Live in Public does his deeply weird story justice. Harris was a pioneer who saw the potential of the internet before almost anyone else, making a fortune in the 1980s, and establishing an internet-based TV network called Pseudo.com. He made millions, but the most interesting aspect of Harris's story comes later, when he blew his money on a series of artistic social experiments, including a Big Brother-style bunker, in which the participants' every action was captured on video. That bunker was where Harris and his fellow inmates spent the turn of the millennium, before the police raided the location in the belief that some kind of cult had been established, prompting him to take the same idea in a more personal direction. Harris and his girlfriend moved into a house in which every action was monitored by cameras, and they began interacting with the online community who watched them, until the whole business inevitably soured their relationship and led to an extremely unpleasant on-camera breakup. Director Ondi Timoner has been filming Josh's various ventures on and off for over fifteen years, and he gives us a compelling warts-and-all portrait of a brilliant visionary and a very complex man. We Live in Public is well-paced and full of extraordinary footage, and at a time when people are revealing more of themselves every day on blogs, Facebook, Twitter and the rest, it's remarkable to see just how far ahead of his time Josh Harris was.

Alexander the Last

Here I am giving Joe Swanberg another chance to impress, and here he is turning in another deeply unimpressive piece of filmmaking. To be fair, this is an interesting advancement for the director in a number of ways. He has drawn on the talents of a few familiar faces – including Jess Weixler and Jane Adams – for this feature, and he has the backing of a producer, Noah Baumbach, who is himself an established filmmaker. Those developments are more interesting in theory than in practice, though, as Alexander the Last remains a thoroughly mediocre and directionless effort. Wexler is a young actress whose husband is out of town, and whose acting partner Jamie (Barlow Jacobs) has temporarily moved in to her apartment while they rehearse their play. This is not a very good idea, as their play involves an intimate sex scene, and the sexual tension between them is complicated by his burgeoning relationship with Alex's sister Hellen (Amy Seimetz). In the film's single impressive sequence, Swanberg cuts cleverly between a scene of Alex and Jamie rehearsing coital positions, and Jamie and Hellen doing it for real. It's the first time I've seen Swanberg show any signs of being a real filmmaker, but that's all Alexander the Last had to spark my interest. I admire what directors like Swanberg are trying to do, with their intimate style, improvised performances and sexual frankness, but more and more I'm finding I like the idea of Joe Swanberg more than the real thing.

Don't Worry About Me

Don't Worry About Me

David Morrissey makes his directorial debut with this low-key film. Don't Worry About Me is an adaptation of James Brough and Helen Elizabeth's stage play The Pool, with the two writers taking on the central roles of David and Tina. He's an enthusiastic dolt who finds himself penniless in Liverpool after making an ill-advised attempt to track down a one-night stand. She's the girl who takes pity on him, and ends up escorting him around the city. The film has echoes of similar romantic two-handers such as Before Sunrise/Sunset and In Search of a Midnight Kiss, but this film is a little rougher around the edges. Morrissey's direction is unfussy and workmanlike but effective, and he makes the most of his surroundings, allowing his characters plenty of room to wander around seeing the sights of the city. Brough and Elizabeth's banter is mostly natural and occasionally witty, even if the picture runs the risk of unbalancing itself with some contrived conflict halfway through. The performances carry it across the odd rocky patch intact, though. Brough is convincing in a surprisingly unsympathetic role, and Elizabeth is marvellous, imbuing Tina with a warmth and sensitivity, and bringing the goods when asked to deliver an emotionally charged monologue late on.

Headhunter

Headhunter

Rumle Hammerich's corporate conspiracy thriller looks and sounds like every other corporate conspiracy thriller of the past twenty years. Lars Mikkelsen is Martin Ving, the go-to guy for companies who need a top employee at short notice, so there's no surprise when he is contacted by the head of the huge Sieger Co., but there is a surprise in store when he finds out exactly what role he is being asked to fill. Mr Sieger (Henning Moritzen) wants someone to replace himself, and he is choosing to go outside the family, skipping over his son Daniel (Flemming Enevold), who was the presumed successor. Soon, Martin finds himself being played by both Stieger and Stieger Jr., with the fate of his own ill son being used to manipulate him. Twists and turns ensue, of course, but the film never manages to get the pulse racing as it plods through various clichéd scenes. It doesn't help matters that so many of the plot developments are pretty hard to swallow – notably the identification of one character from a casual glance at a 35 year-old school photo – and much of Hammerich's writing is clumsy. I was particularly disheartened by the way former journalist Martin's implausible past as a Navy SEAL was tossed into one conversation, purely so he could immediately turn into Jason Bourne when the role required it.

A few weeks ago, I attended a screening of a film called Mary and Max, a brilliant Australian animated film which regretfully doesn't have UK distribution yet. It's the story of a lonely young Australian girl who begins a decades-long friendship by mail with an Aspergers-afflicted Jewish man living in New York. The touching and hilarious story is so involving, and the characters so brilliantly realised, I didn't actually realise the voices were provided by Toni Collette, Philip Seymour Hoffman and Eric Bana until their names had been announced by the closing credits. All of this goes some way to explaining a few of the problems I had with Wes Anderson's adaptation of Fantastic Mr Fox.

A few weeks ago, I attended a screening of a film called Mary and Max, a brilliant Australian animated film which regretfully doesn't have UK distribution yet. It's the story of a lonely young Australian girl who begins a decades-long friendship by mail with an Aspergers-afflicted Jewish man living in New York. The touching and hilarious story is so involving, and the characters so brilliantly realised, I didn't actually realise the voices were provided by Toni Collette, Philip Seymour Hoffman and Eric Bana until their names had been announced by the closing credits. All of this goes some way to explaining a few of the problems I had with Wes Anderson's adaptation of Fantastic Mr Fox.

In Anderson's film, Mr Fox is voiced by George Clooney, and there's no mistaking the actor's presence, as he tosses out smug wisecracks in the central role. The same is true for Billy Murray's Badger, or Jason Schwartzman's turn as Mr Fox's son Ash, and as the puppets used to bring these figures to life don't have the most expressive faces in the world, there's often a strange disconnect between actor and character (Meryl Streep, naturally, seems to overcome this hurdle better than most). So, I didn't really buy into Fantastic Mr Fox as rendered on screen by the director and his talented team of artists, even if I was occasionally amused and impressed by the production, and the idiosyncratic stylistic choices than run through all of Anderson's work didn't bother me as much in this setting as they usually do. Fantastic Mr Fox is every inch a Wes Anderson picture, from the storybook opening and chapter divisions, to the side-on tracking shots and eclectic soundtrack choices.

Thematically, the story fits the Anderson mould too, as the screenplay – which he wrote with Noah Baumbach – leans heavily on daddy issues, with young misfit Ash desperately trying to prove himself to his father, and constantly being outshone by cousin Kristofferson (Eric Anderson). The main strand of the story remains relatively unadulterated, though, even if Anderson and Baumbach have modernised (and Americanised) it in a number of ways. Mr Fox, feeling frustrated in his day job, succumbs to his urge to steal from the nearby farms run by Boggis, Bunce and Bean, despite promising his wife that his days of crime are behind him. The ensuing film consists of a series of set-pieces which are strung together in a sometimes disjointed way. In fact, there's something a little disjointed about Fantastic Mr Fox as a whole. It is an extremely strange film, blending a kid-friendly story with humour that's often too sly and knowing for its own good (the frequent use of the word "cuss" as a substitute for bad language is the most irritating example), and the vast majority of gags fall very flat.

The film's fast pacing and inventive direction keeps it on track, though. In many ways, animation is the perfect milieu for Wes Anderson, whose fastidiously controlled mise-en-scène has sometimes left his live-action features feeling a bit airless. For Fantastic Mr Fox, the director is working again with Henry Selick – who contributed to The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou – and the film's aesthetic has an intentionally jerky, handmade look, perhaps as an old-school riposte to the slick style of most mainstream animations. It takes some getting used to, but Anderson does produce some fine moments and a few witty sight gags, and it suits his desire to fill the frame with tiny details. I'm sure Fantastic Mr Fox will offer many pleasures on DVD, when viewers can freeze the image to pick up on the countless additional touches Anderson has squeezed into view, but while the director has put an awful lot of work into creating this universe, he didn't quite do enough to make me believe in it.

The 53rd BFI London Film Festival kicked off this evening with the world premiere of Wes Anderson's Fantastic Mr Fox, but for some of us, it has already started. A number of pictures have already been screened to the press, and I will soon be writing more expansive verdicts on my favourites from that bunch (The Informant!, The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans and Mugabe and the White African) but here is a brief take on everything else I've seen in the past few days.

Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl (Singularidades de uma Rapariga Loura)

Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl (Singularidades de uma Rapariga Loura)

Manoela de Olivieira is 100 years old and he has been making movies since the early 1930's, but his latest – shamefully – is the first of his films I've ever seen. So I'm not entirely sure how representative of his style Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl is, but I can't say it has prompted me to immediately seek out more of this centurion's work (where on earth would I start?). The film begins with a man (Ricardo Trêpa) relating his tale of woe to a fellow passenger on a train, and over the next hour, we see how his love for the beautiful, mysterious girl who lived across the street (Catarina Wallenstein) turned his life upside-down. Olivieira's filmmaking style is elegant and refined, but there's something awkwardly stilted and theatrical about a number of scenes. This strange element of artifice extends to some of the interactions between characters, but the film remains an oddly intriguing and often beguiling shaggy-dog story, even if it occasionally left me scratching my head.

The Exploding Girl

The Exploding Girl

This slight American independent feature charts the friendship between two uninteresting, inarticulate teenagers, with one half of the pair hoping to edge the friendship into more intimate territory. Zoe Kazan plays the epileptic Ivy, home from school for the holidays and missing her boyfriend, and Mark Rendall is her studious pal; but while the performances are entirely believable, writer/director Bradley Rust Gray gives them very little of interest to do. He keeps the dialogue banal and the emotions muted, but the film is too understated for its own good, drifting aimlessly towards its close without ever doing enough to endear me or interest me in its characters' dilemmas. Frankly, it all grows rather tedious very quickly. Oh, and nobody explodes, disappointingly.

A Single Man

A Single Man

Colin Firth collected the Best Actor award at Venice for this performance, and his guarded, emotionally complex turn as the grieving George certainly impresses. A Single Man accompanies George during one day as he is haunted by memories of his dead lover (Matthew Goode), and spends time with both an old friend (Julianne Moore) and a flirtatious young student (Nicholas Hoult), all the while making meticulous plans to end his life. The film has been adapted for the screen by Tom Ford, who is making his directorial debut, and a very confident first-time effort it is too. The visual style is striking, with Ford draining the colour from scenes in which George appears alone, before slowly bleeding a warm sunlit glow into the image when he makes a connection with someone – it's an effective, if ultimately overused motif. He also employs jump cuts and bold staging, and he successfully finds a balance between George's present-day trauma and the frequent flashbacks. For about half of A Single Man I was riveted, but at some point in the second half, Ford's grip on the material loosens, and it takes a much longer route towards the climax than seemed strictly necessary. The film is never quite as impressive in its latter stages as it is early on, but the ending packs a punch, and it certainly is a solid piece of filmmaking as a whole.

44 Inch Chest

44 Inch Chest

If Don Logan lived to a pensionable age, he might have turned out to be something like Old Man Peanut, the character played by John Hurt in 44 Inch Chest. Peanut is a gangster from the old school, and he's in no doubt about the fate deserved by the young man to whom Colin (Ray Winstone) has lost his wife (Joanne Whalley). Colin's mates have rallied around, and so they all find themselves holed up in a dingy basement, with "Loverboy" tied to a chair while they wait for the distraught cuckold to pull himself together and finish the job. 44 Inch Chest was written by Louis Mellis and David Scinto, the pair behind Sexy Beast, and their new film bears many similarities to that unexpected hit: amusingly profane dialogue, memorable characterisations, and – unfortunately – some shoddy storytelling in the film's second half. A large chunk of 44 Inch Chest takes place inside Colin's increasingly tortured mind, and it's here that the film gets horribly confused with itself, leading to an unconvincing shift in Colin's motivation. First-time director Malcolm Venville does well to maintain a sense of variety in the potentially stagey single setting, but the film's trump card is its cast. Stephen Dillane and Tom Wilkinson are excellent as two of the more understated characters, while Ray Winstone pulls out all of the emotional stops as the despairing central figure, but the film is stolen by the hilarious double-act of Ian McShane and John Hurt, who relish every line of the ripe dialogue Mellis and Scinto constantly serve up for them. This is a flawed film elevated by a terrific cast, and I haven't even mentioned Steven Berkoff's typically...er...restrained cameo appearance.

Hadewijch

Hadewijch

Bruno Dumont's latest stirs up a number of fascinating and typically provocative ideas about the nature of religious devotion, but the director's opaque storytelling sucks away the film's dramatic impact. Giving a compelling performance in the central role, newcomer Julie Sokolowski plays Céline, an utterly devout Christian whose adoration of God consumes her life. When she meets a Muslim teenager (Yassine Salihine), the pair begin spending time together, but she makes it clear that Christ is the only man she has room for in her life. However, a meeting with Yassine's persuasive older brother encourages Céline to question her deeply held beliefs, and to make a life-changing decision which I found rather hard to believe in. Those of us familiar with Dumont's occasionally repellent oeuvre will be primed at this point for something horrible to occur, but the film shies away from ugly shock tactics, and there's a sense of grace in this picture that his work has rarely had before. His fractured, elliptical approach to narrative gets in the way, though, and many of the film's later sequences are ambiguous to the point of confusion. This is Dumont's most interesting and accomplished film for a couple of years, but it falls frustratingly short of its rich potential.

Samson and Delilah

Samson and Delilah

The opening moments of this Australian film play like an aboriginal take on the romantic comedy, but such thoughts quickly dissipate as the story of Samson and Delilah's troubled relationship takes a series of dramatically dark turns. The titular couple (played by Rowan McNamara and Marissa Gibson) are young aborigines who flee their violent domestic lives and head into the city, where simply surviving is a mammoth task. Writer/director Warwick Thornton paints a painfully authentic portrait of lives lived on the margins, and makes potent points about the status of aborigines in Australian society, but the story itself is a little lopsided, and Thornton eventually allows the film to bypass numerous possible endings in an overextended final act. The central characters remain consistently watchable throughout, though, and Thornton allows large portions of the film to play out without a word of dialogue, relying on his young actors to carry the picture with their expressive faces, and both are up to the task. Gibson is a particularly strong presence, as the Delilah who displays the real superhuman strength in this relationship.

Paper Heart

Paper Heart

There's a good movie in here somewhere, a documentary about love in which couples who have been together 30, 40 and 50 years tell us how they met, and how they have managed to keep their love burning over the intervening decades. We get glimpses of this movie throughout Paper Heart, but those glimpses are buried beneath a horribly twee faux-documentary starring the irritating Charlyne Yi. She begins the film by telling us that she doesn't believe in love, and that this movie is her quest to understand it, which is why she spends some time interviewing the couples I mentioned, all of whom have charming stories to tell. But the focus of the film gradually shifts to a fictional relationship between Charlyne and Michael Cera (playing himself - no, really playing himself this time), who begin a romance during the course of filming which suffers under the duress of constant camera surveillance. Quite why Yi and director Nicholas Jasenovec (who hires Jake Johnson to play him on screen) went down this route is unclear, as Yi's constant giggling and lack of screen presence renders the scenes involving her and Cera dull and self-indulgent, and the strained air of manufactured quirkiness quickly grates.

During the current wave of cinematic fascination with vampires, the bloodsuckers have been appearing in a variety of forms. A hit adaptation of Stephanie Meyer's Twilight (soon to receive a sequel) has made vampirism appealing for teenage girls; Tomas Alfredson's Let the Right One In has earned critical adulation and will soon be remade for in America; while Alan Ball's TV series True Blood has brought the creatures into our homes. Even that wide array of offerings couldn't prepare us for Park Chan-wook's Thirst, however. Park's take on the vampire film is typically distinctive, marked by his boundless stylistic verve and gallows humour, and he is determined to reject or toy with many accepted vampiric clichés. His characters have reflections in mirrors, they don't sprout fangs, and the vampire's aversion to crucifixes is dealt with head-on, by making the lead character a catholic priest.

The priest is Sang-hyeon (Song Kang-ho), and his problems arise after he suffers a crisis of faith and makes the drastic decision to submit his body to medical science. The experiments he undergoes prove to be disastrous, and after breaking out in horrendous boils and vomiting torrents of blood, he dies on a gurney, before a transfusion of infected blood brings him back from the dead. It's an inexplicable plot development, and that's not the only question raised by this expository opening, which is handled by Park in a rushed and vague manner. In fact, the film only settles into some kind of consistent rhythm when Sang-hyeon starts to come to terms with his new life as a vampire. As a moral man, the priest refuses to kill in order to feed his thirst, and he compromises in amusing ways, sucking small doses of blood from a comatose patient's drip while doing his rounds at the hospital. But bloodlust isn't the only new urge Sang-hyeon has to try and control, as his sexual lust for the mousy, downtrodden Tae-joo (Kim Ok-vin) suddenly comes to the boil, sparking a passionate and ultimately destructive relationship.

Park's story is loosely based on Émile Zola's great novel Thérèse Raquin, with Tae-joo suffering in an unhappy marriage to a sickly husband (Shin Ha-kyun), and living above the shop run by his domineering mother (Kim Hae-sook). Tae-joo spends her nights running barefoot in the streets as fast as she can, in incidents she passes of as sleepwalking to her husband and mother-in-law, but she has nowhere to run to, until Sang-hyeon offers her an unlikely escape route. Their relationship is the lifeblood of Thirst, not least because Park has found in Kim an actress capable of remarkable emotional range, convincingly transforming herself from a meek, withdrawn housewife into a blood-crazed monster with stunning rawness and conviction. Song Kang-ho's performance as Sang-hyeon is a solid one, which warms up after a dour start, but Kim is a sensational find, and I couldn't take my eyes off her.

There's enough interesting chemistry between Song and Kim to give this occasionally maddening picture some emotional weight, and the use of Thérèse Raquin as the basis for Thirst's narrative was a wise one, with some of the best sequences (notably a night-time murder, and the lingering guilt) adhering closely to key scenes from the book. The director doesn't always stick to this narrative, though, and the various disparate plot points and digressions he grafts onto his central thread leave the film seeming bloated and unfocused. Too often, an exhilarating sequence will be followed by an aimless one, which drags the whole picture down. At times, it's easy to believe that Park isn't entirely sure where the story is taking him, although he does manage to pull off an extended climactic sequence that is clever, funny and oddly poignant.

Essentially, though, Thirst is another bravura demonstration of the director's undeniable virtuosity and innovation as a visual stylist, and it will be up to the viewer to decide whether that compensates for the problems with pacing and story. The film is stunningly designed, with Park's regular cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung delivering transfixingly gorgeous images that match his superb work on Sympathy for Lady Vengeance, and the sound design is just as impressive. Sang-hyeon's evolution into a vampire results in heightened sensory perception – picking up minute sounds as if they were taking place right next to his ear – but the most vivid noise in the film is the sound of blood being slurped from a body, which sent a shiver down my spine. Technically, Park is a master of his craft, but there's the constant, nagging sense that the aesthetics of his picture continue to take precedence over the basics of storytelling coherence. When Tae-joo insists that Sang-hyeon paint the walls, floor and ceiling of their apartment white, she claims it's because she wants to create the illusion of daylight, but we all know it's simply because Park wants the visual shock of dark red splashing against pure white. There's nothing necessarily wrong with a filmmaker favouring style over substance, of course, but when a filmmaker is in possession of the gifts that Park has, it's a shame the style frequently outpaces the substance by such a margin.

Sally Potter's Rage gathers together an exciting, eclectic cast, and wastes it on a silly and self-indulgent cinematic experiment. The conceit here is that an unseen, unheard character named Michelangelo is attending a fashion event, and interviewing various participants on his mobile phone as part of a school project. The film therefore consists of a series of monologues straight to his camera, in front of garishly coloured backgrounds, and through their unedited speech the characters reveal their insecurities and obsessions as well as exposing the shallow and morally dubious nature of the fashion industry. This is hardly revelatory stuff, though. Potter's jabs at the emptiness of this industry are predictable and tired, and hardly strong enough to sustain a feature-length film. Rage might have worked well enough as a short, but at 95 minutes it feels painfully overextended, with Potter's initially intriguing approach quickly feeling like a tiresome gimmick. The limitations of Potter's setup tell in the second half, when a series of deaths take place off screen – we hear them but we don't see them, because Michelangelo keeps his camera pointed at his subjects – but who would honestly resist turning their camera to where the action is? Surely the era of YouTube and mobile phone video has taught us that our compulsion is to look, not turn away?

Sally Potter's Rage gathers together an exciting, eclectic cast, and wastes it on a silly and self-indulgent cinematic experiment. The conceit here is that an unseen, unheard character named Michelangelo is attending a fashion event, and interviewing various participants on his mobile phone as part of a school project. The film therefore consists of a series of monologues straight to his camera, in front of garishly coloured backgrounds, and through their unedited speech the characters reveal their insecurities and obsessions as well as exposing the shallow and morally dubious nature of the fashion industry. This is hardly revelatory stuff, though. Potter's jabs at the emptiness of this industry are predictable and tired, and hardly strong enough to sustain a feature-length film. Rage might have worked well enough as a short, but at 95 minutes it feels painfully overextended, with Potter's initially intriguing approach quickly feeling like a tiresome gimmick. The limitations of Potter's setup tell in the second half, when a series of deaths take place off screen – we hear them but we don't see them, because Michelangelo keeps his camera pointed at his subjects – but who would honestly resist turning their camera to where the action is? Surely the era of YouTube and mobile phone video has taught us that our compulsion is to look, not turn away?

All Rage ultimately has to offer is a great cast, and some of them do enough to sell this thing as well as they can. Judi Dench's cynical fashion critic and Steve Buscemi's seen-it-all war photographer were highlights for me, and I was also impressed by some of the younger actors on show, notably the Shakespeare-spouting David Oyelowo and Lily Cole, whose extraordinary features were made for close-ups. Most of the actors have moments when they come close to elevating the thin material they have been handed, but by the end of the film it has all just collapsed into one meaningless, incoherent noise. Sally Potter has used Rage to explore the new distribution possibilities that the internet has opened up for low-budget films, but whatever method you choose to watch a movie, the only questions that matters is "Is the film any good?" In this instance, the simultaneous release of Rage in cinemas, on DVD, via the internet and mobile phones simply means there are many more ways to avoid it.

In the hands of another filmmaker, Fish Tank might have been just another grim British feature about broken lives, broken dreams and social ills. Under the careful direction of Andrea Arnold, however, the film grows into something far more complex and resonant; her vibrant visual sense and ability to coax note-perfect performances from her cast elevating the film beyond its overly familiar setting. One of those actors is a young woman named Katie Jarvis, who has no previous acting experience and was spotted by Arnold arguing with her boyfriend, displaying the kind of fire she knew Fish Tank's central character would possess. Arnold decided to take the gamble, casting this unknown in a demanding role alongside experienced, talented actors, and the gamble has paid extraordinary dividends. Jarvis is a revelation.

She plays Mia, a 15 year-old who lives with her mother (Kierston Wareing) and her mouthy younger sister (the scene-stealing Rebecca Griffiths) on a drab East London housing estate. On first glance, Mia looks like a stereotype; abrasive, troublesome, expelled from school and prone to picking fights. But Jarvis shows us other aspects to her character in private moments. When she's alone, Mia loves to dance, practicing her moves in an abandoned flat. To be honest, for all her enthusiasm, she's not particularly good, but she clings to this dream in the hope that it will offer her a future. She is also a character far more vulnerable than her brash demeanour suggests, and she is touchingly ready to drop aggressive front as soon as someone – anyone – offers her with some semblance of kindness or respect.

One person who has such an effect on Mia is Connor (Michael Fassbender), the charming Irishman her mother brings into their home. From the way Connor looks at Mia, and the way he behaves towards her, we instantly begin to suspect some ulterior motives on his part, but Fassbender – giving the latest in a string of outstanding performances – plays the character with skilful ambiguity. Arnold frequently teases our expectations before undermining them in interesting ways. Shooting in a 1.33 aspect ratio, Arnold's work with cinematographer Robbie Ryan is intimate and sensually alive; as in her impressive debut Red Road, she imbues many sequences with an erotic charge, notably when Mia and Connor are in close proximity, and she slows the camera down to let the moment linger.

Fish Tank is a more rounded and accomplished film than Red Road, which eventually buckled under the weight of its plot contrivances, and it's definitely a step forward for Arnold, but I still have some slight reservations about her work. Her filmmaking style throws up as many longueurs as it does memorable moments, and Fish Tank is a film that would have benefitted from some more disciplined editing. The director also has a weakness for clumsy symbolism (a chained white horse, for example), and she is prone to making some baffling decisions, such as a bizarre dog reaction shot that undermines one of the film's most poignant sequences. More often, however, Fish Tank is a striking, honest and gripping film, never more so than in the climactic half-hour, when Arnold stages a terrifically tense sequence that reminded me of the Dardenne brothers' best work. It is during this sequence, as we watch we breathless anticipation, that we realise just how much we have come to care about the character Jarvis and director have so vividly created, and the film's touching, open-ended climax, leaves us wondering what life has in store for her next.

The Last Days of Emma Blank (De laatste dagen van Emma Blank)

The Last Days of Emma Blank (De laatste dagen van Emma Blank) Shirley Adams

Shirley Adams The French Kissers (Les beaux gosses)

The French Kissers (Les beaux gosses) Plan B

Plan B Karaoke

Karaoke J'Accuse (1919)

J'Accuse (1919) Underground (1928)

Underground (1928) Surprise Film

Surprise Film